Tomorrow 83 new doctors are starting at our hospital and we're running orientation activities over the next 10 days. The team have been working hard on the preparation and there’s a buzz in the air now it’s close. I’m sure the new members of our profession will be feeling that tonight too. Their mixture of excitement and trepidation is well placed. I remember only too well my first intern job. There’s a lot to learn and tons of personal growth to be had. The dry run of being a student just doesn’t compare to when the rubber hits the road for real.

One of my talks is called ‘Medicine, our way’ and I’m pretty frank about some of things that Medicine is not doing very well right now and what we need from our doctors of the future. Among the talk are 7 tips for success - they sound pretty easy and if you have a lifetime to perfect them, they certainly are.

#1 High quality and compassionate health care

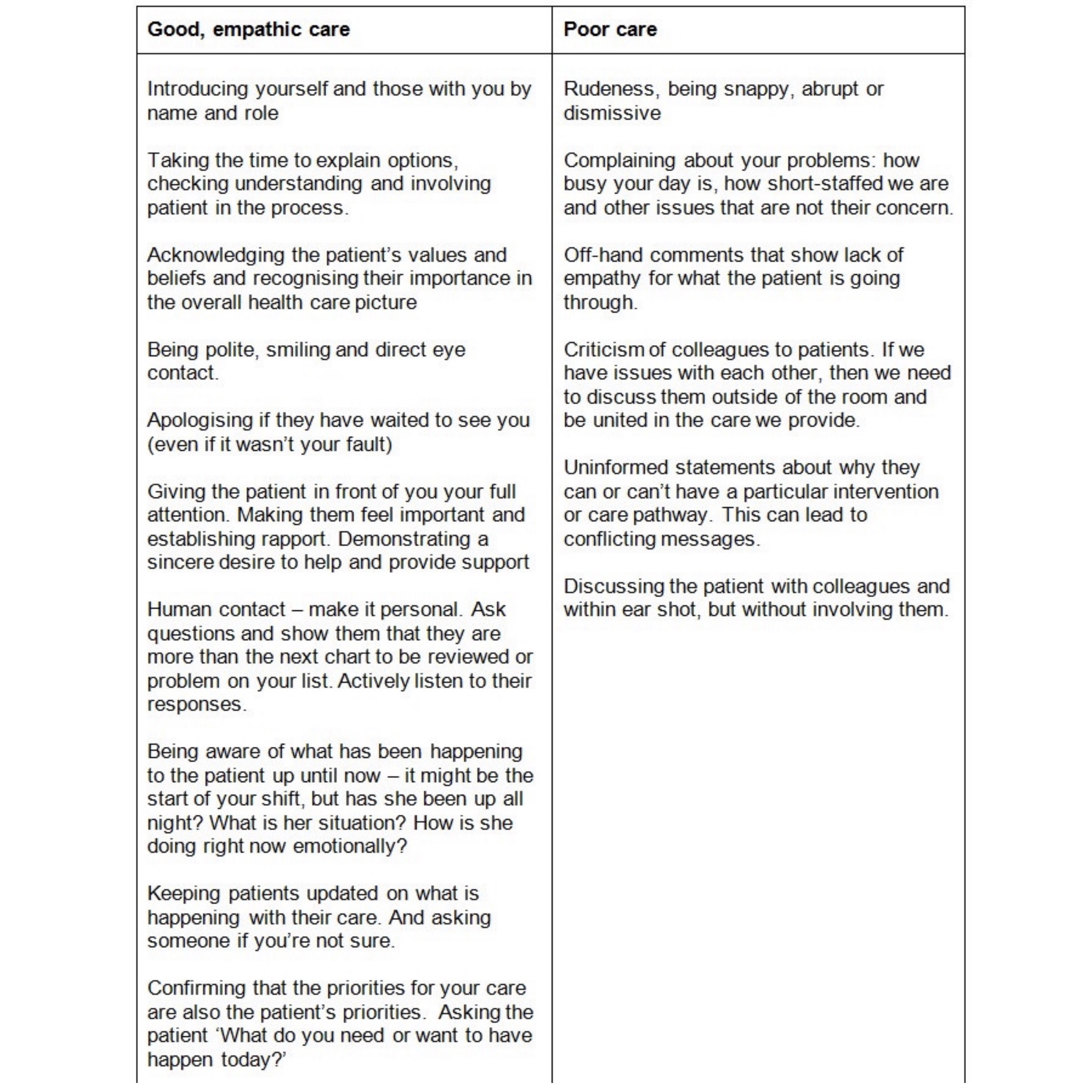

More than anything medicine needs this. Both of them. All the time. Quality care is definitely about being very good at doctoring – up to date knowledge, diagnosing, procedures and following best practice guidelines. Unfortunately, medical practice doesn’t always make it easy for caring health professionals to do what our patients need most (more on that later).

Organisational priorities sometimes don’t feel the same as the patients and we’re pulled every which way by a system that can feel like it shifts at one speed: glacial. You can change this. Medicine needs articulate, empathic communicators and an approach to the craft that embodies compassion and kindness. Genuine, heartfelt, like-you-would-want-your-mother-treated, care and attention. It’s simply why we are here.

#2 Our colleagues are our most valuable asset

We need to look after each other. We need one other for debriefing, learning and sense-making of the really hard stuff we are a part of each day. Do not underestimate the part you play in your colleagues work lives, or the role they might have in your own.

Here you see Dr Turner during simulation training we did in obstetrics. Grant is an anaesthetic specialist, we get along well, but we're not best mates. We have a shared experience in the workplace that means we trust each other implicitly. If he calls me and says 'I think the surgeon needs help in theatre 5', I’m there. If I call him from Birth Suite and ask for a theatre because a baby is distressed, I know he will move heaven and earth to find me one. These are the relationships we need to nurture in our work.

The Health LEADS framework is a way of looking at healthcare skills, one that move us beyond the core skills of obstetrics or anaesthesia or cardiology. We need a shared language of how we lead ourselves, how we engage with each other and bring about positive change into the systems in which we work - no matter how diverse they might seem. Our colleagues really are our most valuable asset.

#3 Create a positive culture

The culture of an organisation includes those unwritten little rules about how people treat each other. We all need to feel genuinely valued and respected for what we do. But there's responsibility on us too. There are negative cultures in all of society these days. Brené Brown talks about scarcity culture, where the two loudest questions we hear in life (and often within ourselves) are: what should I be afraid of, and whose fault is it? We can buck this trend with positivity, a willingness to be vulnerable and a true belief in our own self-worth.

Take accountability. Treat others with respect. Assume the best of people - even when you might have evidence of the opposite. Compassion gives you the vision to see through someone’s behaviour to the truth behind it. Usually it’s grounded in an unconscious fear that they are unworthy. Smile and say good morning to strangers. Complement often - take the time to actively look out for something positive that a colleague did and acknowledge them personally. We can’t recipe good culture, but we can make a difference within our range of influence.

The second image here is a note written by medical students to the surgical interns last year and stuck on the surgery ward notice board. Emotional intelligence like this inspires me.

#4 Centre your patient

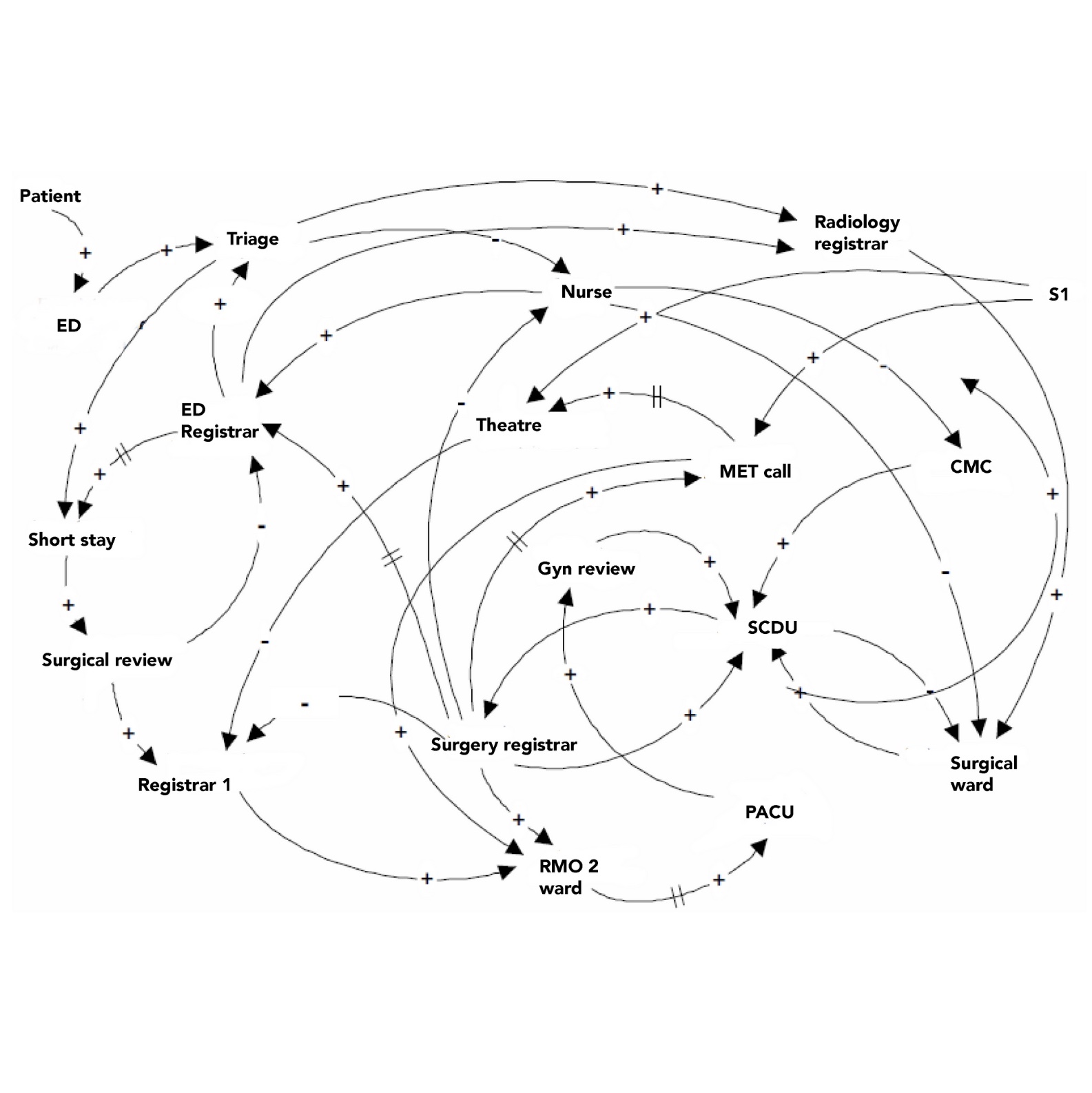

Health care is increasingly complex and patients have lots of medical problems. The system we have in healthcare wasn’t designed from the ground up to cope with this situation. Organ-based specialties and sub-specialties add to the problem. As do individual egos. You can help your patients navigate their way through by doing what is best for each one as individuals. Unfortunately, often the system doesn’t make this easy, but when we centre our patient, the necessary course of action is usually clear.

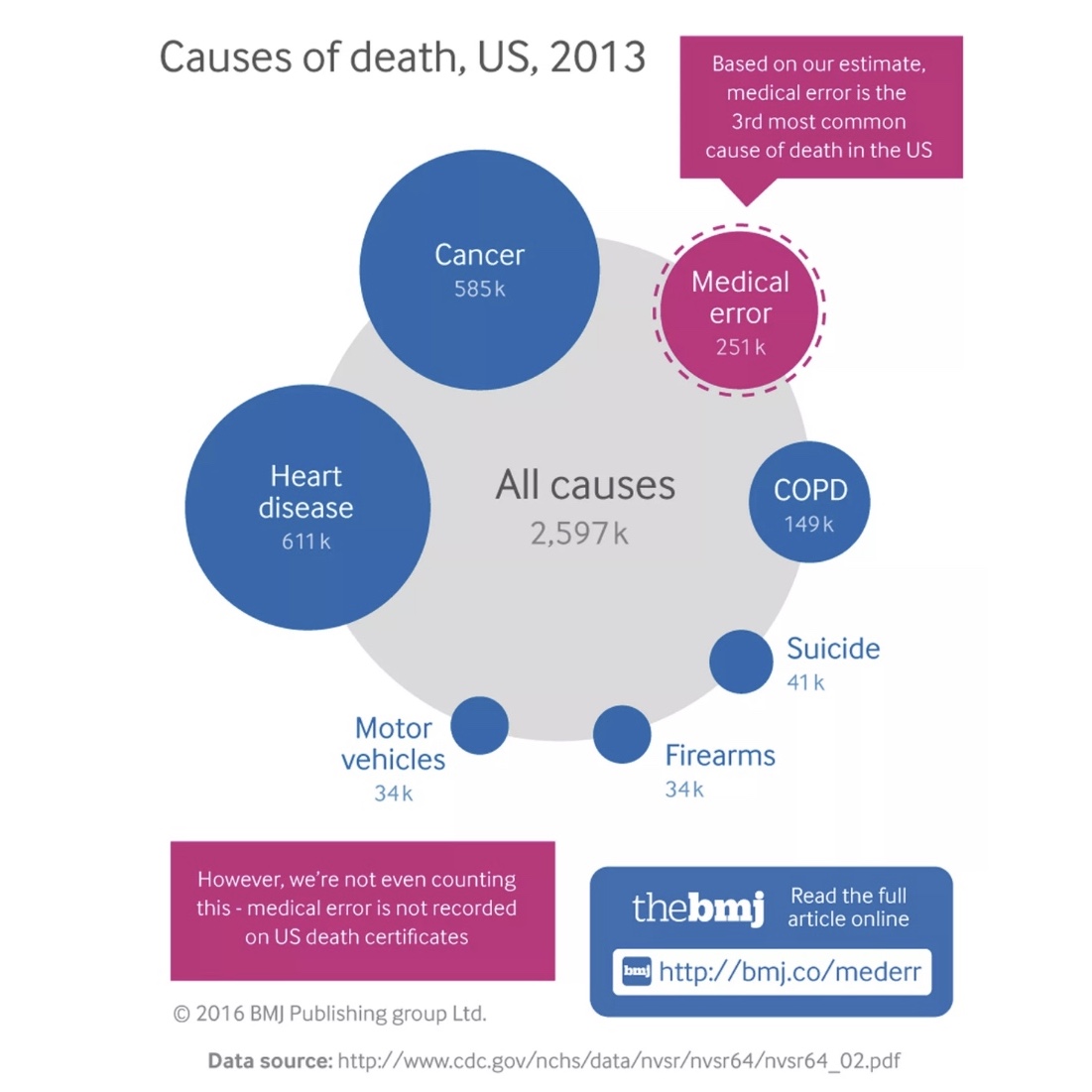

We are all busy and the focus shifts quickly from patient care to workload management - it has to. But what is your patient’s experience so far? What needs do they have? What are their priorities? Cross-team and interdisciplinary communication, discharge planning and keeping everyone updated. Sadly we often get it wrong - the 2016 BMJ publication is from US CDC data, and there’s little reason to believe that Australia is substantially different.

Although organisational charts are a hierarchical structure, healthcare is a complex adaptive system and it needs professionals with specific skills. Small changes in how you show up as an individual can make big changes in the system. And keep your patients safer. Emotional intelligence is key.

#5 Unsure? Ask

When you're unsure, contemplate carefully and don't hesitate to ask those around you. You're going to face many difficult decisions, but none of us are expected to know it all. There are no stupid questions and there's a whole network of people here to support your practice and development.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a human cognitive bias. These biases are something we're all subject to - it’s not about you as an individual. You're going to start to feel confident over the coming years, but just keep in mind that confidence often precedes expertise. We're in a high stakes business and it's sensible to seek advice from seniors, especially in high risk areas. Learn what these are for your area of practice, and you'll have your back covered. Be humble and document everything!

#6 You will make mistakes

The amazing Advanced Trainee, you know - that one who inspires you, who knows everything about everything. He failed his exams twice - and he sent someone home with a PE last year. That surgeon who has crazy slick laparoscopic skills - 15 of her first 20 majors were converted to open because she couldn’t do it.

Every single one those people you admire, failed their way to success. Welcome to the fail club. None of us is immune. But we’re inspired, and we know that all things worthwhile involve determination and persistence.

We crave to do our best, but know that when life knocks us, we need to embrace the lessons, and grow. Medical practice comes with a degree of safety. There’s always someone around to help, and systems full of resilience, so failure rarely equates with disaster. But it still hurts. We’re here to help you get used to it. It gets easier, especially when you realise the amazing things you can achieve.

#7 Invest in yourself

You have a long life ahead, and you're going to learn a lot of medicine and technical skills. Don't forget your personal development - working on yourself, constantly growing. And definitely don't limit it to medical texts. Remember the LEADS framework - Leads self and Engages others are two of the most important domains. Read non-medical books, learn about metacognition, cognitive biases and the mental models of people different to you. Listen to podcasts, read novels, be open to new ideas and thinking differently. We are all a work in progress. Good luck!