So, why did you become a health professional? To make people better? To cure disease, reach the top of your field? Because your family pushed you? Or perhaps it was to relieve suffering in the world?

I honestly don't always feel that I cure many people. Don't get me wrong, of course, I'm pretty good at this doctoring gig - I've got a few years behind me now. But am I part of a system that consistently makes people better? When there's a fetal bradycardia in labour, and we rush around and heroically deliver the baby by a swift caesarean section, and the cord artery pH is 6.9, and the baby recovers fully after a few days in NICU - yes I'm pretty sure that we did what we are meant to.

But what about this statistic from a British Medical Journal article a few years ago? I don't think that it's got much better since then and I know for a fact that Australia's figures for iatrogenic patient harm are not much better. 1 in 9 patients experiences a complication due to healthcare, 1 in 4 of those who are admitted to hospital.

Third highest cause of mortality?

But if we are the third-highest cause of mortality, there's a whole bunch of morbidity beneath that too. I've spent a lot of time working with the Patient Safety team in our hospital, and I see it there. What about all the distress and anxiety that doesn't lead to actual harm? We spend our time working out how to make people better, but how do we invest in not making them worse?

The word patient is from Latin and means 'one who suffers' - and in my time spent in medicine, I've come to realise that I can do so much more good for the world when my aim every day is to alleviate suffering, rather than just to try and cure disease.

Preventing suffering

Our patients are suffering from their disease (inherent suffering), and they experience avoidable suffering from an imperfect healthcare system. They suffer because we fail to acknowledge disease-inherent suffering, because we treat them like a disease rather than a person, when we don't make eye contact when we are busy, if we don't go down to their level when speaking, when we talk about them in earshot, when we don't compassionately reach out to touch them. They suffer because we don't treat their time as being as important as ours, if we don't reduce anxiety through reassurance, when we don't pre-empt stressful situations and prepare or guide them. They are harmed when we fail to do a correct handover to our colleagues and if we fail to provide continuous care.

Compassionate, connected care

So many of these harms can be avoided by simple, compassionate and connected care. Connected as in we make sure that everything essential to the patient is handed over and gets done. I say simple, but although the acts are often simple, remembering their importance or prioritising them is challenging when you are stressed, short of time and work in a system that sometimes makes it difficult.

When I take that patient across to the operating theatre and her baby's heart rate has been at 50 beats per minute for the last 9 minutes, I reassure her that we are taking good care of her and that she will be fine. I tell her that the anaesthetist is Dr Ford and that she's a great doctor - I'd be happy to have her do my anaesthetic. I tell her and her partner that their baby will be okay. When we've delivered her baby, the resus was successful, and she's waking up from the general anaesthetic, I call her husband who is anxiously waiting in the Birth Suite, to let him know as soon as possible that they're both doing well.

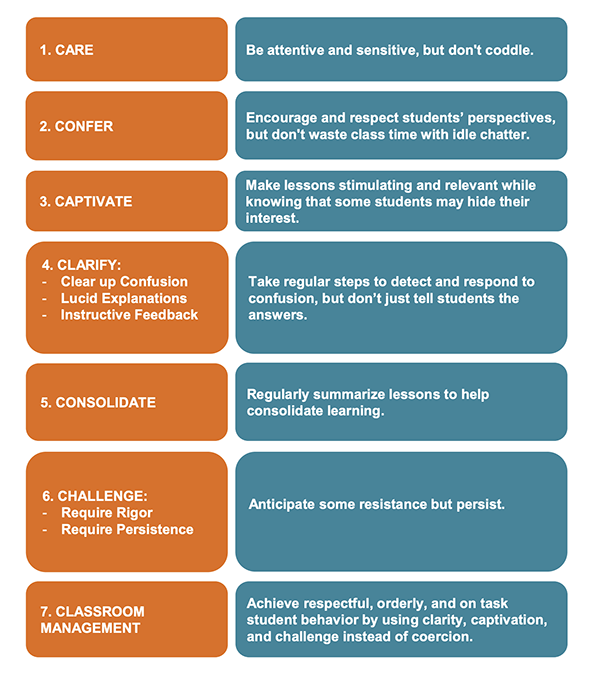

Relieving suffering by understanding what patients need is something we can all do. It doesn't take lots of medical training, just an awareness - firstly that it's important, and secondly, how to approach it. Here are more specifics from a book by Christina Dempsey - The Antidote to Suffering.

The unwritten curriculum of healthcare

Have a think about how you can do this when you are pushed by a system that may set you up to fail - because you're so busy and it is so complicated and often lacks coordination. By an unwritten curriculum in healthcare that goes against what you are trying to achieve. I'm talking about a culture of:

Negative attitudes of teachers

Legal phobia

Electronic health records that consume your attention and time

Mocking of 'difficult patients'

Team silos within medicine and horizontal violence

You can do better than this and you can still enjoy working in health. I'm still enjoying it and I'm inspired by a generation of new professionals who want change and are willing to step up and make it happen. Health professionals who feed the fire inside from day one and keep working at it throughout their career.

Dr Danny Tucker